It was a trip back to the basics to remind us what these arguments are really about in the end, while also forcing us to question not to accept.įascinating experience of the lines drawn between various disciplines and their goals- how the idea that "that's someone else's job" has very real effects in the formation of ideas. mostly because he's there, to borrow a phrase. This time, we are being trained to think of ourselves as peers, whose job it is to show the main behind the curtain well. This time we bypassed that discussion entirely, taking it for granted as established and agreed on, and concentrated on dissecting the arguments presented on their structure and substance, in a close analytical read that sought to draw on our knowledge of history to poke holes in his argument. This time, I'm in an international history program, filled with historians. I don't think we discussed the validity of his claims at all, but rather focused on place they had in world events and history and how these ideas could affect our daily lives. We were essentially diplomats in discussion, preparing our strategy of attack against the other side's claims. The last class I read this for was called "Uses of History in International Affairs," and we spent the majority of our time talking about history as an act- history as narrative, history as an agenda, what someone might use these statements for. UPDATED: Amazing how reading this for a different class brought out a totally different discussion.

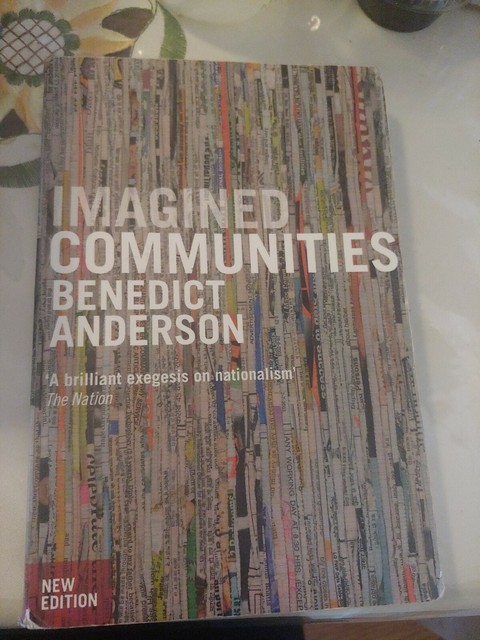

This revised edition includes two new chapters, one of which discusses the complex role of the colonialist state's mindset in the develpment of Third World nationalism, while the other analyses the processes by which, all over the world, nations came to imagine themselves as old. He shows how an originary nationalism born in the Americas was modularly adopted by popular movements in Europe, by the imperialist powers, and by the anti-imperialist resistances in Asia and Africa.

In this widely acclaimed work, Benedict Anderson examines the creation and global spread of the 'imagined communities' of nationality.Īnderson explores the processes that created these communities: the territorialization of religious faiths, the decline of antique kingship, the interaction between capitalism and print, the development of vernacular languages-of-state, and changing conceptions of time. What makes people love and die for nations, as well as hate and kill in their name? While many studies have been written on nationalist political movements, the sense of nationality-the personal and cultural feeling of belonging to a nation-has not received proportionate attention.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)